Endurance: Survival lessons from Lumet

Thursday | April 21, 2011 open printable version

open printable version

I don’t believe in waiting for the masterpiece. Masterful subject matter comes up only rarely. The point is, there’s something to advance your technique in every movie you do.

DB here:

Across half a century he outpaced his contemporaries. He was the last survivor of the vaunted 1950s generation of East-Coast TV-trained directors, men who went over to theatrical films just as the studio system was in decline. John Frankenheimer, Martin Ritt, Richard Lester, and Franklin J. Schaffner won big projects early on, but they also faded faster. As they were moving out of the game in the 1970s and 1980s, Lumet was getting his second wind. He ground movies out–good, so-so, or wretched–like a contract director of the studio days. Sometimes he had a strong stretch, as in the early 1980s, and sometimes not. He started in his early thirties with Jean Vigo’s cameraman Boris Kaufman, shooting crystalline black and white. At the end he was making a feature in high-definition video.

When Lumet died on 9 April, journalists were generous in their praise. But most of the eulogies seemed to me constraining. They overlooked his complicated role in postwar American film, and they neglected to supply the sort of historical context that make even his negligible films of interest. Concentrating on his official masterpieces (Dog Day Afternoon, Network), the obituaries cast him as a hard-nosed urban realist. That’s part of the story, but if we want a fuller picture of this long-distance runner, we need to trace his path in more detail. That in turn can teach us something about shifting generational opportunities in American cinema.

We can start by noting what the recent accolades seem to have forgotten: at the start of his career Lumet faced brutal hostility from the critical intelligentsia that ruled his home town.

Danger man

The Pawnbroker.

Reading 1960s film criticism, you might think that Sidney Lumet was the biggest threat to film art since the Hays Code. Young cinephiles today may be unaware of the vituperation that New York’s highbrow critics showered on him at the start of his career.

John Simon: “What is Lumet good at? Intentions, underlining, and casting.”

Manny Farber: “Giganticism is, of course, the main Lumet contribution [to The Group]. . . . Miss [Shirley] Knight, in a concentrated post-coitus scene atop [Hal] Holbrook’s chest, has a head the size of a watermelon.”

Andrew Sarris: “The Pawnbroker is a pretentious parable that manages to shrivel into drivel.”

Most tireless was Pauline Kael, who throughout the decades picked off nearly every Lumet movie with the casual contempt of Annie Oakley shooting skeet. From the backhanded compliment (“The Pawnbroker is a terrible movie and yet I’m glad I saw it”) to the eviscerating dismissal (Deathtrap is “an ugly play and what appears to be a vile vision of life”), Kael did not relent. She found Lumet’s staging “slovenly,” his color schemes inept; in Serpico “scene after ragged scene cried out for retakes.”

The hunt was in full cry in Kael’s 1968 essay, “The Making of The Group,” one of those behind-the-scenes journalistic forays that always end in tears for the production. Every such think-piece mysteriously assures the film’s commercial failure, while guaranteeing that posterity will remember each participant as a knave or a fool. Yet for sheer bloodthirstiness, Kael’s reportage easily surpasses that of her predecessor Lillian Ross in Picture.

Kael is out to show that the conditions of acquiring, producing, and marketing films have become almost utterly corrupt. No artist can survive the system. So she starts by establishing Lumet as merely a journeyman, shooting the script as a straightforward job of work.

But then things get rough. He is, for one thing, a poor craftsman.

He cannot use crowds or details to convey the illusion of life. His backgrounds are always just an empty space; he doesn’t even know how to make the principals stand out of a crowd . . . . Lumet is prodigal with bad ideas . . . . He will take the easiest way to get a powerful effect; in some conventional, terribly obvious way he will be “daring” . . . The emphasis on immediate results may explain the almost total absence of nuance, subtlety, and even rhythmic and structural development in his work. . . . I was torn between detesting his fundamental tastelessness and opportunism and recognizing that at some level it all works. . . . Because Lumet can believe in coarse effects he can bring them off.

He is also a severely deficient human specimen.

[He was] the driving little guy who talked himself into jobs . . . He seems to have no intellectual curiosity of a more generalized or objective nature . . . For Lumet, a woman shouldn’t have any problems a real man can’t take care of . . . . He’ll go on faking it, I think, using the abilities he has to cover up what he doesn’t know.

Kael has her generous moments, praising Long Day’s Journey into Night (1962), chiefly because of the performers, and in later years she would admire scenes in Dog Day Afternoon (1975). But usually her admiration boomerangs into a complaint (Lumet yields a fast pace, but that makes him slapdash). On the whole she and her Manhattan peers, who seldom agreed on anything, conceived Lumet as dangerous.

Why? Partly because they mostly set themselves against the middlebrow culture of the newspapers and newsweeklies. Many of Lumet’s early films were admired by staid critics. Praise from these quarters was anathema to the sophisticates. Somebody had to tell the Times’ Bosley Crowther that The Pawnbroker (1965) was not “a powerful and stinging exposition of the need for man to continue his commitment to society.”

Another strike against Lumet was his pedigree. He was said to have brought TV technique, simultaneously bland and aggressive, to theatrical cinema. Early live TV drama, confined by the home screen’s 21-inch format and weak resolution and hamstrung by punishing shooting schedules, pushed directors to rely on flatly staged mid-range shots, goosed up with close-ups, fast cutting, and meaningless camera movements.

Kael suggests that Frankenheimer, a common foil to Lumet at the period, managed in films like The Manchurian Candidate (1962) to convert the TV look into “a new kind of movie style,” though she never explains what that consists of. By contrast, Lumet simply followed the line of least resistance, emptying out his shots and “hammering some simple points home.”

There’s nothing on the screen for your eye to linger on, no distance, no action in the background, no sense of life or landscape mingling with the foreground action. It’s all there in the foreground, put there for you to grasp at once.

The TV style threatened to suffocate the glories of cinema: the full view, a more leisurely unfolding of action, a sense of life flickering on the edges of the plot. For Kael the TV-trained Lumet exemplifies the loss of the great tradition of artistic moviemaking personified in Jean Renoir.

Lumet was dangerous in another way. He seemed part of a trend toward heavy-handed showoffishness. Partly the trend was seen in the sweaty strain of Method acting, typified in Kazan’s work. Manny Farber proposed that the Method was at the center of the “New York film,” a fake realist package predicated on psychodrama, arty compositions, and liberal pieties. 12 Angry Men was “counterfeit moviemaking,” filled with “schmaltzy anger and soft-center ‘liberalism.’” Hard-sell cinema, Farber called it. Dwight Macdonald saw the same bludgeoning in The Fugitive Kind.

Lumet’s direction is meaninglessly over-intense; lights and shadow play over the close-up faces underlining lines that are themselves in bold capitals; every situation is given end-of-the-world treatment.

The new tendency toward self-conscious artifice didn’t just have New York roots. The French New Wave’s somewhat disjunctive cutting, unexpected camera movements, freeze-frames, and other flagrant techniques made audiences and filmmakers aware of film style to a new degree. Tony Richardson, John Schlesinger, and other directors scavenged these devices to give their films an up-to-date panache. Once more a critic needed to invent a new label for Lumet: Macdonald claimed that he was an exponent of the Bad Good Movie, “the movie that is directed up to the hilt, avant-garde wise,” in the vein of Mickey One, The Servant, The Trial, and the work of Godard. The Pawnbroker’s fragmentary flashbacks led Sarris to call it Harlem mon amour.

Harsh as they are, these comments do have a point. The early films shout and scream a lot, both dramatically and pictorially. Lumet admitted his love of melodrama, conceiving it not simply as overplaying but rather as conflict at the highest pitch of arousal: extreme personalities in extreme situations. So a silence is usually prelude to an outburst, and a bellow or a slap is never far off. The jury deliberations in 12 Angry Men (1957) become a group therapy session (or an Actors Studio class?) in which bigots must confess their traumas.

Stage Struck (1958) and The Group (1966) are pictorially innocuous, perhaps partly because they were shot in color, but The Fugitive Kind (1960) is a banquet of elaborate lighting effects whipped up by Kaufman. Macdonald wasn’t fair in his dismissal; the film is dominated by medium and long shots, with close-ups held in reserve for big moments, and the line readings don’t seem to me as overbearing as he suggests. Still, there is a sense of pressure, with very precise reframings and sets densely packed (mirrors, curtains, staircase railings) in a way that accords well with Williams’ overripe dialogue. There is an upside-down shot, and at some moments, as Macdonald notes, the illumination lifts or drops in magical ways—a surprise gift, Lumet claims, from Kaufman.

As a pluralist, Lumet would stage some scenes in full shots and long takes, sometimes at a surprising distance from the camera. But it was hard not to notice the other extreme. His most famous black-and-white films mixed in tight close-ups, oppressive sets, wide-angle distortions, and chiaroscuro. 12 Angry Men is relatively subdued in this regard, building toward more looming images at the climax, with some powerfully jammed ensemble frames.

Fail-Safe (1964) surrenders itself to flamboyant shot design once we get into the war room and then into the President’s sealed chamber. Contra Kael, as in 12 Angry Men, many of these shots have busy backgrounds, albeit not of the Renoirian sort.

The Pawnbroker (1965) is Lumet’s most famous orgy of strident technique, with Sol Nazerman nearly as caged at his counter window as he was in the camps. Even more overwrought is The Hill (1965) in which short lenses pump officers’ raging faces into gargoyle shapes, with pores and welts and gobs of sweat thrust under our noses.

In sum, this is not the director eulogized in Entertainment Weekly: “He never tried to dazzle audiences with flash and style.”

What critics didn’t note, however, was that the more outré look cultivated by Lumet, Frankenheimer, Ritt, and company fitted fairly snugly into 1950s Hollywood black-and-white dramatic style. The blaring deep-focus and violent close-ups exploited by the TV-born directors were already visible in the work of Mann (The Tall Target, 1951, below), Aldrich (Attack! 1956, below), Fuller, and many other directors.

During the 1950s what we might call roughly the “post-Welles” look was well-established for serious subjects and genre pictures alike. The Hill pushes things a bit, as Frankenheimer did in Seconds (1966), but the cramped, low-angle style on display in Lumet’s early work is part of a tradition that goes back years (and which had its echoes in many overseas directors, such as Bergman and Fellini). The wilder reaches of that style, it now seems clear, belonged to Fuller and company, not to mention the Kubrick of Strangelove and the Welles of Touch of Evil. Like Richardson, Schlesinger, and others, the TV émigrés may have gotten their wrists slapped for trying to map onto prestigious social-message movies the visual pyrotechnics already acceptable for program pictures.

Not incidentally, some directors had already found the wide-angle deep-focus look useful in their TV productions. Below are frames from Requiem for a Heavyweight (directed by Ralph Nelson, Playhouse 90, 1956); The Defender (directed by Robert Mulligan, Westinghouse Studio One, 1957); and Lumet’s own omnibus program Three Plays by Tennessee Williams (Kraft Television Theatre, 1958).

You can argue that their move to cinema actually smoothed out the directors’ style. The less square frame and bigger scale of the theatre screen made films like Frankenheimer’s debut The Young Stranger (1957) more spacious and relaxed than what could be seen on the box. 12 Angry Men was a polished effort, starting with an elaborately staged six-minute crane shot assembling the cast in the jury room, and using the width of the screen to enclose several faces. Looking back, we can see that Lumet offered something quite close to then-current Hollywood norms, and it looked less crude than what would be found on live TV of the period.

Still, The Pawnbroker and other films can be credited (or blamed) with helping spread the in-your-face style that would come to dominate American cinema of the next fifty years: disjunctive editing, slow motion, the arcing tracking shot (The Group), handheld shooting for moments of violence or anguish, glum color schemes (preflashing for The Deadly Affair), the teasing flashbacks that will be gradually filled in. Lumet’s early films are anthologies of most of today’s tics and tricks.

Yet by the time of his death, the director who was once feared as the vanguard of something new and awful had come to embody something old and trustworthy. Somehow the unambitious journeyman and pretentious copycat became a “classicist.”

How did that happen?

A prince of the city

Before the Devil Know You’re Dead.

Instead of indicating that he was joining or extending a tradition, Lumet reacted to the hailstorm of criticisms with surprising equanimity, at least in the interviews he gave so abundantly throughout his career. He was modest, acknowledging that many of his films turned out to be feeble, and he declared himself a learner. He tried different projects, he said, to improve himself. He wanted to learn to manage color, to work in different genres (e.g., the dark comedy Bye Bye Braverman, 1968), eventually to fall in love with digital video capture. To some extent Lumet changed because he really wanted to learn more and explore various sides of moviemaking.

Lumet always claimed that he didn’t apply a personal style to his projects; he tried to find the best way to handle the script. He thereby confessed himself to be what auteur critics of the 1960s were calling a “metteur-en-scène,” the director who judiciously enhances the material rather than transforming it to suit his personality. This was probably a good survival strategy in the new churn of the 1970s.

The mid-1970s was the Great Barrier Reef of American cinema. Virtually no members of Hollywood’s accumulated older generations, from Hitchcock and Hawks through the 1940s debutantes (Wilder, Dmytryk, Fuller, Siegel) and the 1950s tough guys (Aldrich, Brooks) to the TV émigrés, made it through to 1980. Many careers just petered out. The future belonged to the youngsters, the so-called Movie Brats. In this unfriendly milieu, Lumet fared better than most. He tried a semifarcical heist film (The Anderson Tapes, 1971) that mocked the rise of the surveillance society, with everybody wiretapping and taping and videoing everybody else. He mounted a classic mystery (Murder on the Orient Express, 1974), a musical (The Wiz, 1978), and a free-love romance (Lovin’ Molly, 1974). Of the items I’ve seen from these years, the most daring is The Offence (1972). This study of a sadistic British police inspector’s vendetta against a child molester offers a sort of seedy expressionism. In another gesture toward psychodrama, long conversations with the perpetrator reveal that the copper is a bit of a perv himself.

Lumet’s most successful rebranding took place in a sidelong return to the Pawnbroker milieu: low-end, location-shot, crime-tinged social commentary using New York theatre talent. Filming in color and casting off the baroque precision of the earlier work, he made his compositions more casual and his shot changes less precise. His cutting pace picked up: six seconds on average for Serpico (1973), five for Dog Day Afternoon (1975), both courtesy of the high priestess of the quick cut, Dede Allen. The driving tempo of these movies gave them an urgency that critics could tie to the ticking-clock plots, the atmosphere of urban pressure, and of course the extroverted acting of Al Pacino.

With the two crime films, and the satiric Chayefsky talkfest Network, Lumet remade his image. He was a New York filmmaker, offering raucous, hard-nosed, semi-cynical takes on corruption in the police, the justice system, politics, and the media. His protagonists tended to be Jews, Italians, and Irish, all working stiffs or bare-knuckle power brokers; and the enemy, again and again, turned out to be the Ivy elite. A tailor-suited WASP, male or female, was likely to sell you out. Only ethnic minorities knew the real score. The line could come from almost any mid-career Lumet film: “I know the law. The law doesn’t know the streets.”

The crowning achievement in this vein, for critics if not for audiences, was Prince of the City, a sprawling study of a cop’s patient years of taping and informing on his corrupt colleagues. More slowly paced than the earlier urban dramas, the film also marked Lumet’s move toward something else again. The style was drier and more sober, almost passive, emphasizing static and somewhat distant setups; the cutting slowed down to nearly nine seconds on average. As mid-period Lumet had blotted out the early years, now something more calm, even comparatively austere, came into view.

Whatever the project, however, by the later 1980s he was offering his own alternative to the fast-cut, whirlicam style that was bewitching young filmmakers. While directors in all genres were building scenes out of endless choker close-ups and cutting every four or five seconds, Lumet applied the brakes, lingering on two-shots, letting whole scenes play out in full frame, moving his actors around and ordaining a cutting pace close to ten seconds on average. The first eight minutes of The Verdict (1982) consist almost entirely of long shots and extreme long shots. The protracted takes and antic bodily contortions of Deathtrap might have come from a French boulevard farce; the first tight single of Christopher Reeves is delayed for half an hour. In an age in which critics decried the choppy confusion of tentpole action, the plainness on display in movies like Running on Empty (1988) and Night Falls on Manhattan (1997) looked anachronistic. Right to the end, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007) could spare a lengthy and distant shot to register a high-end drug boutique and shooting gallery. We had come from the Hysterical Lumet by way of the Gritty Lumet to the Restrained Lumet.

Acting in the frame

Yet he did not milk the urban crime vein dry. He continued to try a wide range of projects, even probing the Red Scare in Daniel (1983). The rationale was chiefly performance. Lumet was an “actor’s director.” He demanded at least two weeks of rehearsals, which included not only table readings but eventually full blocking of scenes, including fights and chases. Derived from his TV and theatre days, the method suited his belief that actors needed a firm structure in order to invent their characters. Interestingly, this actors-first rationale can be adjusted to any phase of the rough stylistic development I’ve plotted. The high-pressure facial shots of the early films can highlight the minutiae of the performances. But so can mid-shots that let actors build in bits of business.

Manny Farber praised the moment when Fonda in 12 Angry Men dries his fingers at length, one by one. It shows, Farber says, “the jury’s one sensitive, thoughtful figure to be unusually prissy” and provides a “mild debunking of the hero.” But it’s not the unintegrated detail Farber claims; Fonda’s coldness is set up early in the film, when he stands remotely from his peers and shows no interest in them as men. And Fonda was always a master of finger-work, which Lumet could exploit in fastidious framings. In Fail-Safe as the President tries to halt the bombers rushing toward the USSR, Fonda projects the man’s minutely controlled apprehensions by pausing to rub his fingertips together, off in the corner of the shot.

This micro-gesture suddenly leaps, as Eisenstein might say, into a new quality: a worried facial expression.

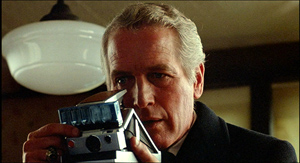

More explicit is the characterizing moment in The Verdict when Frank Galvin (Paul Newman) starts his day with a sugar donut and a full glass of whiskey. The setup is concise: He has crossed off the wakes he’s visited, and his palsied hand can’t pick up the glass without spilling some.

So Frank checks to see if anyone is looking before, like a dog, he bends his head to slurp off a little.

It’s a simple but powerful image of degradation, far removed from the trembling mouth and bulging brows of Steiger in The Pawnbroker.

Lumet cared as much for camera technique as for acting maneuvers. His book Making Movies provides a virtual manual of movie style as draftboard engineering. His gearhead side was probably another legacy of the buccaneering days of live TV and the New-Wave inspired awareness of artifice. He took inordinate pride in his “lens plots” and lighting arcs, charting purely technical changes that would weave their way through the film. (In this he was ahead of his time; now most filmmakers develop these technique arcs, or at least they say they do.) Despite this almost mechanical conception of technique, though, late Lumet rediscovered a bare-bones simplicity of performance and framing that was willing to risk looking flat. In Daniel, he lets the angry young man whose sister has wasted away into madness confront the poster agitating for their dead parents. No tracking in, no circumnambulating camera, no heightened cuts or nudging score. And no need to see Daniel’s face. Susan merely lifts her head.

It’s as if the visual rodomontade of the Movie Brats drove Lumet toward a new sobriety. When Galvin is preparing to try the case of the girl left in a coma through medical malpractice, he visits the hospital and takes Polaroids of her inert body. The slowly developing images not only give us the fullest view of the girl we’ve had so far. They also come to suggest his dawning realization that this is more than just a chance for big money.

Galvin starts to grasp that letting the hospital settle out of court will allow the officials to write off their mistake. There is a human cost to simply getting the check. If he does it, he will now be a better-paid ambulance chaser. Yet he doesn’t stand valiant for truth; the drunk is scared, drained of dignity, and he clutches his portfolio as a sad, ineffectual shield.

Offered the money, Frank takes out the photos and weighs them against the check. Then with a sigh of exhaustion, contemplating the fool’s crusade he’s launching, he returns the check and drops the pictures into his bag.

Very simple visual storytelling; it might have come from a 1930s movie. But this stark presentation of moral decision, given as a straightforward framing of a man’s body, achieves a measure of artistic nobility in a year that gave us Porky’s and Rocky III.

Telling it all, holding some back

Prince of the City.

It’s good to remember such moments of pictorial storytelling because Lumet’s films, especially the early ones, tend to be gabfests. If Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, and Paddy Chayefsky, along with the Method acting tradition, are your coordinates, you will be drawn to chatterboxes and blowhards. Lumet loved the spoken word, which was after all the mainstay of live TV (“illustrated radio,” it was sometimes called). It’s not clear that he ever shook the habit. His characters usually step onstage leaking exposition, announcing their pasts, their personalities, their plans, and their deepest feelings. This has the advantage of making plot premises clear, but it reduces the figures’ mystery and their ability to surprise us, or to complicate our feelings about them.

Sometimes Lumet did let story construction do heavier lifting. It happens in The Pawnbroker, because the nearly catatonic Nazerman speaks so little that the fusillade of flashbacks provides his backstory. More daringly, the large-scale back-and-fill of The Offence, peppered with small memories but also looping around the central incident in the interrogation room, seeks to reveal Sergeant Johnson’s affinities with the suspected child murderer. We need to remember Lumet’s early fondness for time-shifting plots before we declare Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead an old guy’s effort to catch up with Pulp Fiction.

Even without benefit of broken timelines, Lumet could occasionally hold back information to reshape our first impressions. Take the central revelation of Dog Day Afternoon, when cuddly Al Pacino reveals that his “wife” is not the woman he’s married to (a nice plot feint here) but the man whom he loves. This apparently sensationalistic twist comes early enough to modulate into pathos when Pacino’s character dictates his two wills.

Prince of the City realigns our sympathies in a more intricate way. At the start, Danny is presented as a tormented soul. We’re led to think that he turns snitch because of things we see: the invitation to go undercover, his brother’s and father’s angry concern that his pals are crooked, and above all the shameful efforts he makes to get drugs for his informant. Once he turns, however, he can’t limit the investigation, and at nearly the end his treachery has broken the most important ties in his life.

But “nearly the end” is the operative term, because Prince of the City boldly appends a ten-minute epilogue showing Danny being investigated himself. The Danny we saw at the film’s beginning may have been steeped in corruption; the drug bust we saw included, behind the scenes, a major ripoff of money; he has lied more than we realized; and it seems likely that he cheated on his wife with the prostitutes whom he supplied with drugs.

A modern filmmaker, or Lumet in his bodacious early mode, might have spiced these flat testimony scenes with lurid flashbacks. But sticking simply to Danny’s feeble, evasive stonewalling raises questions of his own vulnerability. Having watched him break down over years and having heroicized his suffering to a considerable degree, we have to judge him anew. Is he simply too weary to fight the charges, or has he been caught out? The ending might seem to allow for cynicism, but we can’t cast off our respect for what Danny has risked.

Further, Lumet intercuts the court scenes with government meetings about whether to prosecute Danny. In the manner of a Shavian problem play, this tactic obliges our sympathies to be clear-eyed. If The Verdict lays all its cards on the table and invites straightforward sympathy for Galvin, Prince of the City, by hiding major aspects of Danny’s character and circumstance, leads us to a more nuanced experience. The narrational dynamic of the film invites us to rethink our protagonist’s actions and decide whether to grant him mercy.

In the vanguard of a new style in the 1960s, Lumet remade himself as part of the 70s renaissance. That freed him to cover nearly every bet on the board, and some paid off. As hotshot younger directors sped past him into tentpole territory, he put the independent sector to use–financing through presales, working with stars on the way down and on the way up, releasing the films through boutique distributors, trying many options with a stubborn pragmatism. He handled failure, ignoral, and disdain better than probably any of us could. “Though his films are invariably flawed,” wrote Sarris in 1968, “the very variety of the challenges constitutes a sort of entertainment.” This zigzag career trajectory provides a unique, even heartening EKG of success and survival in the modern American film industry.

At the same time, he helped make audiences and critics more conscious of film technique, in ways both salutary and damaging. He was part of my film school: The very first movie I saw in a theatre during my freshman year of college was The Pawnbroker, and I revisited it several times. Here was a modern instance of “pure cinema,” worth comparing with A Hard Day’s Night and 8 1/2. (Yes, I hadn’t seen much.) Prince of the City has drawn me since I first saw it in a moldy two-screener in Florida and thought: “Can Hollywood have made a Brechtian film?” I leave for another time the tale of watching Prince in a nearly empty screening sponsored by Nick Cave.

You can probably tell that Lumet is not my favorite filmmaker. Several of his movies I earnestly hope never to see again, and even the ones I admire contain moments I would wish otherwise. But he has given me unique pleasures and prodded me to ask some questions that intrigue me. More broadly, I can’t understand the failures and accomplishments of modern American film without taking into account this marathon man.

For this entry, I haven’t managed to see or re-see as much of the Lumet output as I’d hoped, but the twenty-three films I revisited include his most famous titles (except for The Wiz, which might better be called infamous). My comments here supplement those I make about Lumet and his generation in The Way Hollywood Tells It, 145-147.

I’ve drawn my critics’ quotations from anthologies of their writings. The one I should probably signal explicitly is Pauline Kael’s “The Making of The Group,” in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (Little, Brown, 1968). The piece is dated 1966, but I can’t prove that it was actually published then. I find it endlessly interesting, not least because it may help us trace some origins of critical clichés. I’m thinking not only of the art/ business dyad but also the appeal to Renoir as the prototype of the spontaneous film creator. Ironically, for at least some projects we have evidence that Renoir rehearsed his actors quite a bit and retook scenes until he was satisfied. Double irony: Somewhat before Kael was celebrating the careless grace of Renoirian spontaneity, he had in Testament of Dr. Cordelier (1959) turned to a multicamera technique for his own television project. Renoir and Lumet intersect in unexpected ways!

On live TV shooting methods, a succinct overview can be found in Erik Barnouw, Tube of Plenty (Oxford, 1975), 160-166, and of course Gilbert Seldes’ Writing for Television (Doubleday, 1952), which I’ve praised elsewhere on this site. Seldes scatters some intriguing comments on live TV drama through his The Public Arts (Simon and Schuster, 1956). Just as important, Criterion continues to serve film studies by releasing precious documents from early television. Watch the items included in The Golden Age of Television and the three Lumet/ Williams playlets folded into Criterion’s Fugitive Kind box to see what these directors were up against, and with what relief they must have greeted the wider choices available on film.

The indispensable sources on Lumet are the fine collection Sidney Lumet Interviews, ed. Joanna E. Rapf. It’s here that Gavin Smith can be found sketching a case for Lumet as continuing classic Hollywood while also pressing into “80’s modernism” (132). And of course everyone must read Lumet’s own Making Movies. On editing The Pawnbroker, see Ralph Rosenblum and Robert Karen, When the Shooting Stops… The Cutting Begins: A Film Editor’s Story (Penguin, 1975), 145-166. Glenn Kenny has an excellent 2007 interview with Lumet on digital techniques in the DGA Quarterly.

Credits: Stage Struck; Night Falls on Manhattan.